- Why RBAC Matters in Project Software

- RBAC, Simply Defined and How it Maps to Projects

- How RBAC Actually Looks in a Project Platform

- The RBAC Model in a Bit More Depth

- RBAC vs ABAC vs ACL: Which Model Fits?

- Implementing RBAC in a Project Management Tool

- Best Practices Without the Buzzwords

- Common Pitfalls and How to Avoid Them

- RBAC Examples You Can Adapt

- “RBAC Meaning,” Definitions, and a Brief Glossary

- A Realistic Checklist, Described in Prose

- Conclusion

RBAC (role-based access control) is an authorization model where permissions are attached to roles that represent job functions, and users receive those permissions by being assigned to those roles. Instead of deciding, one person at a time, who can create projects, update tasks, view reports, or approve budgets, you define a small, stable set of roles (Project Manager, Team Lead, Contributor, Client) and manage access through those roles. In a project management platform this approach turns a messy collection of object-level tweaks into a predictable, auditable system that scales as teams and workloads grow.

Why RBAC Matters in Project Software

Project management tools are central reservoirs for task discussions, files, time logs, budgets, and client data. Without a clear access model, two problems appear quickly. The first is over-privileged users: people see and do more than they should simply because it felt convenient during onboarding. The second is fragile exceptions: one-off permissions granted on individual tasks or folders that nobody remembers six months later. RBAC solves both by putting control where it belongs – at the level of job responsibilities. That reduces risk, accelerates onboarding and offboarding, and makes audits far less painful because you can answer “who can do what?” by inspecting roles rather than chasing scattered object settings.

RBAC, Simply Defined and How it Maps to Projects

RBAC links three primitives. Permissions are the atomic actions your tool understands – view task, comment, create project, edit deadline, delete file, approve invoice. Roles are bundles of those permissions that mirror real job functions. Users are people who are assigned one or more roles and inherit the permissions those roles carry. Many platforms add role hierarchies, so a Senior PM can automatically do everything a PM can, and constraints, so conflicting powers (like requesting and approving the same spend) never end up in the same hands. In day-to-day project work, RBAC becomes the blueprint for who can see which projects and tasks, what they can change, and which parts of the workspace are entirely out of view.

How RBAC Actually Looks in a Project Platform

Most organizations converge on a compact role catalog. An Owner or Admin configures global settings, security, and billing and rarely participates in routine project work. Project Managers set up projects, invite people, assign work, adjust scopes and dates, and generate status and workload reports. Team Leads coordinate execution inside their projects: they shape tasks, reassign work within the team, and keep delivery on track without touching workspace-wide settings. Contributors update status, log time, comment, and attach files; they are accountable for progress but do not control budgets or project membership. Clients or Approvers see only the projects shared with them; they can review deliverables and leave comments, but they cannot quietly browse unrelated work or alter schedules. The labels may differ, but the logic is consistent: design roles around responsibilities rather than around individuals, and reserve object-level exceptions for genuine edge cases with an explicit reason.

The RBAC Model in a Bit More Depth

Users, Roles, Permissions

Think of users as principals that need access; they may even include service accounts that automate imports or reports. Roles are named job functions that a layperson could understand from a single sentence in your handbook. Permissions are the verbs exposed by your tool. When a user holds more than one role, their effective permissions are the union of those roles. This makes change management straightforward: to modify what a group of people can do, you adjust the role once instead of editing dozens of individual accounts.

Role Hierarchies and Constraints

As teams grow, hierarchies prevent duplication. If a Senior Designer routinely does everything a Designer does plus a few extra tasks, let the former inherit from the latter and document the difference explicitly. Constraints keep the system honest. Separation of duties is the classic example: the person who requests a budget increase should not be the same person who approves it; the analyst who prepares a report should not be the one who signs off on it. RBAC gives you a neutral language to encode those principles without personalizing them.

RBAC vs ABAC vs ACL: Which Model Fits?

RBAC vs ABAC

RBAC is job-based: membership in a role grants access. It is easy to explain, quick to administer, and predictable to audit. ABAC (attribute-based access control) decides at request time by evaluating attributes of the user, resource, action, and environment. An ABAC rule might say that employees whose department equals Sales can view contracts in their own region during business hours from approved networks. ABAC is more expressive and can reduce role count, but it is also harder to design and troubleshoot, because you are debugging policy logic instead of checking a simple role assignment. A pragmatic pattern is to adopt RBAC as the baseline and layer ABAC only where context truly matters, such as location limits for sensitive documents, device posture checks for financial data, or temporary conditions during an incident.

RBAC vs ACL

ACLs (access control lists) attach permissions directly to individual objects: this person can read this file, that person can edit that task. ACLs are excellent for surgical exceptions, but they do not scale. As the number of projects and artifacts grows, a forest of object-level grants becomes unmanageable and impossible to audit reliably. RBAC scales because permissions live in roles rather than in every object; you change a role once and the effect propagates everywhere the role applies. Many mature systems combine both: RBAC provides the default posture, and ACL-style sharing is used sparingly for special cases with clear owners and review dates.

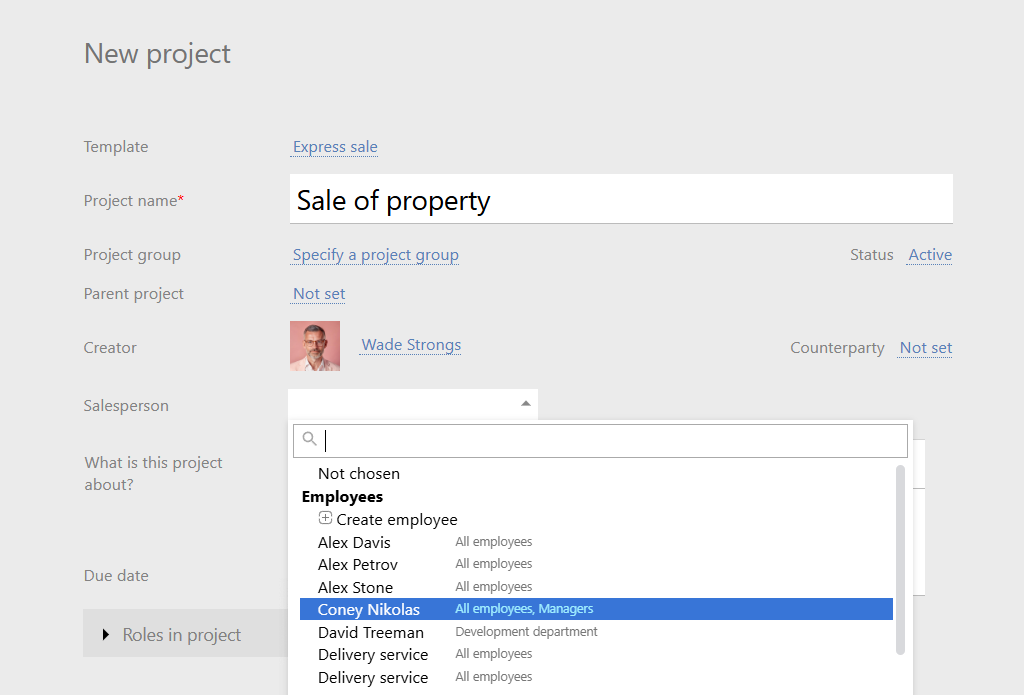

Implementing RBAC in a Project Management Tool

Begin with a short inventory of the resources you care about (projects, tasks, files, reports, time logs) and the actions your platform supports. Then design a minimal role set that reflects how work truly happens today, not how you wish it happened. Fewer roles are better; four to six well-named roles will cover the majority of scenarios in most teams. Write a one-sentence purpose statement for each role to keep it grounded in reality.

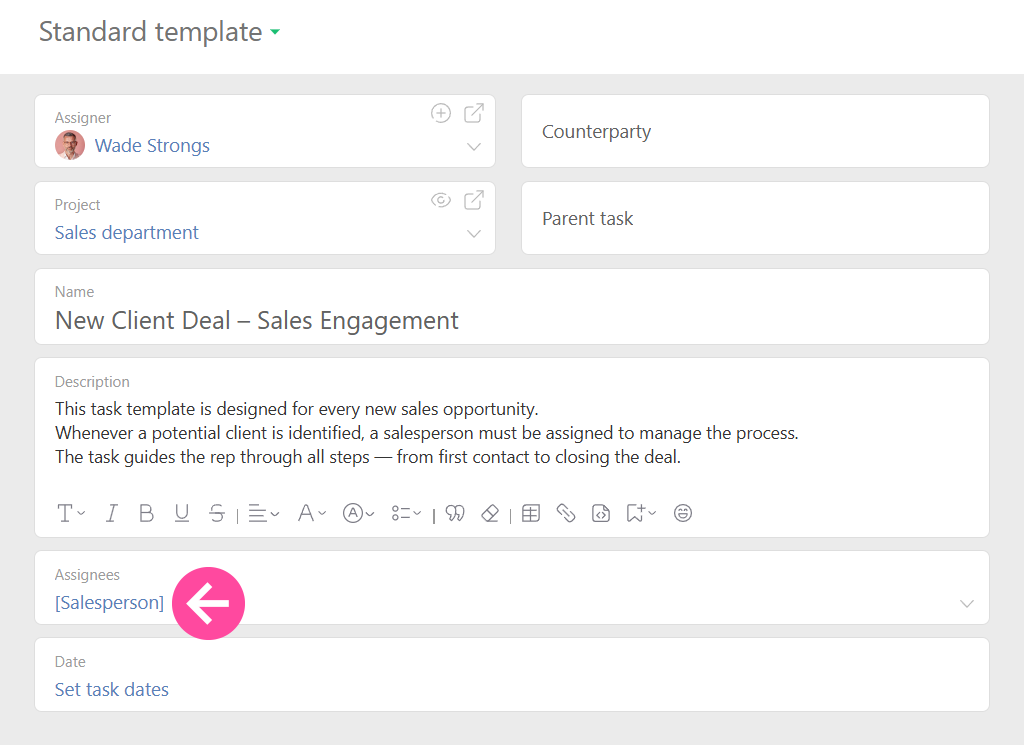

Next, map permissions to roles deliberately. Use the platform’s permission matrix to confirm what each verb really means, and test borderline cases where visibility might be inherited – participants on a task, for example, often gain wider read access than administrators expect. Involve functional leads in a quick review: ask each whether the proposed role grants enough to do the job and nothing that would be surprising to their peers. Assign users to roles via groups owned by team managers; this makes onboarding and offboarding routine operations rather than special projects.

Pilot the configuration on a contained project. Walk through realistic flows: a Project Manager creates a new project and invites members; a Team Lead defines tasks and adjusts priorities; Contributors update progress and log time; a Client reviews deliverables. Preview what each actor can see and do, including the client view, and confirm that confidential work truly stays hidden. Fix surprises while the surface area is small. Only then roll out to the rest of the workspace.

Finally, add rhythm. Schedule quarterly reviews of elevated roles and membership in sensitive groups. Prune inactive accounts, remove obsolete privileges after reorganizations, and record the changes. If your platform supports impersonating a user or previewing access as a role, use that during reviews to verify the effective state rather than trusting configuration screens.

Best Practices Without the Buzzwords

The principle of least privilege is not a slogan; it is a habit. Grant the minimum necessary permissions, and treat exceptions as temporary until proven otherwise. Keep your role catalog small and your role definitions crisp, with a single owner responsible for each. Prefer role inheritance to duplicating permission bundles. Separate duties in workflows that affect money, compliance, or customer trust. Document intent in plain language so new administrators can reason about the design without reverse-engineering it from toggles. And audit regularly – pick a few representative users, view the workspace through their eyes, and confirm they see exactly what they should and nothing else.

Common Pitfalls and How to Avoid Them

Role sprawl is the silent failure mode. When every unusual request produces a new role, you accumulate overlapping definitions that nobody fully understands. Consolidate similar roles, retire those that solved one-time problems, and handle truly rare situations with time-boxed object shares reviewed on a schedule. Privilege creep is the second trap. People change teams, yet their old roles linger; months later they still have access to plans they no longer need. Tying role assignment to groups owned by team managers helps, because membership changes ride along with team changes. A third mistake is ignoring how object-level visibility interacts with your RBAC design. Task participants, followers, or auditors may inherit visibility in ways that bypass your intent; learn those rules in your tool and align defaults accordingly. The last, and most avoidable, is neglecting the client view. Invite external stakeholders only after you have seen precisely what they will see.

RBAC Examples You Can Adapt

Here is a neutral pattern that works in many teams. Owners and Admins are few and trusted; they handle systemwide concerns (billing, authentication, security posture) and do not interfere with everyday project work. Project Managers create and close projects, curate membership, assign and reschedule tasks, and generate workload and status reports. Team Leads coordinate execution within their projects; they can shape tasks and redistribute work inside their scope but have no special powers elsewhere. Contributors are the heartbeat of delivery: they update task status, log time, comment, and attach files. Clients or Approvers have a narrow window into the workspace; they can review and approve deliverables and comment on discussions shared with them, but they cannot browse unrelated projects or alter deadlines. None of this depends on a particular vendor. These are RBAC ideas expressed in the language of projects and tasks.

If your organization also uses cloud platforms, you may recognize the same pattern at larger scales. A role definition (a named set of permissions) is assigned to a principal at a specific scope, and the effect is consistent across thousands of resources. That mental model transfers cleanly to project tools and can guide how you name roles and document their boundaries.

“RBAC Meaning,” Definitions, and a Brief Glossary

If you need a compact definition for training materials or an AI Overview box, use this: role-based access control is a model where permissions are tied to roles, and users gain those permissions by being assigned to those roles. The term “what is RBAC” almost always refers to this job-based arrangement. When someone asks for “rule-based access control,” clarify whether they actually meant role-based, or if they are thinking about ABAC, which evaluates attributes and rules at decision time. Keeping the vocabulary clean prevents configuration mistakes later.

A Realistic Checklist, Described in Prose

Treat implementation as a short arc rather than an endless project. Start by writing down the resources and actions that matter. Draft four to six roles that mirror how teams truly operate today, and describe each in a sentence that anyone on the team could understand. Map permissions to those roles using the platform’s matrix and verify borderline behaviors where visibility might be inherited. Assign users through groups so onboarding and offboarding are predictable. Pilot on one project, preview access from each actor’s point of view, and correct surprises. Roll out once the pilot feels boring – in a good way. Then put reviews on a calendar and actually run them: remove elevated roles that are no longer justified, retire unused exceptions, and confirm that clients only see what they should.

Conclusion

Ready to put RBAC to work? Define your roles, map them to permissions, then preview access from a user’s point of view. In Planfix you can manage this from Access management, refine Permissions, and keep visibility tidy across Projects and Tasks. Once the baseline is stable, invite clients with limited access and revisit roles quarterly – the small effort pays back in safer, faster, more accountable teamwork.

Why not give it a try right now?

Planfix offers a full-featured trial version of the product for 14 days.